Laryngeal papilloma is an uncommon condition caused by the human papilloma virus. It typically involves type 6, 11, 16 and 18 and most commonly affects the vocal cords. Being a viral infection, it is presumed that the initial seeding from the disease comes either through airborne transmission or via the bloodstream. It is only rarely genuinely transmitted in the form of typical sexually transmitted infection. Unfortunately, there is a lot of stigma through the literature suggesting that laryngeal papilloma is predominantly a sexually transmitted infection.

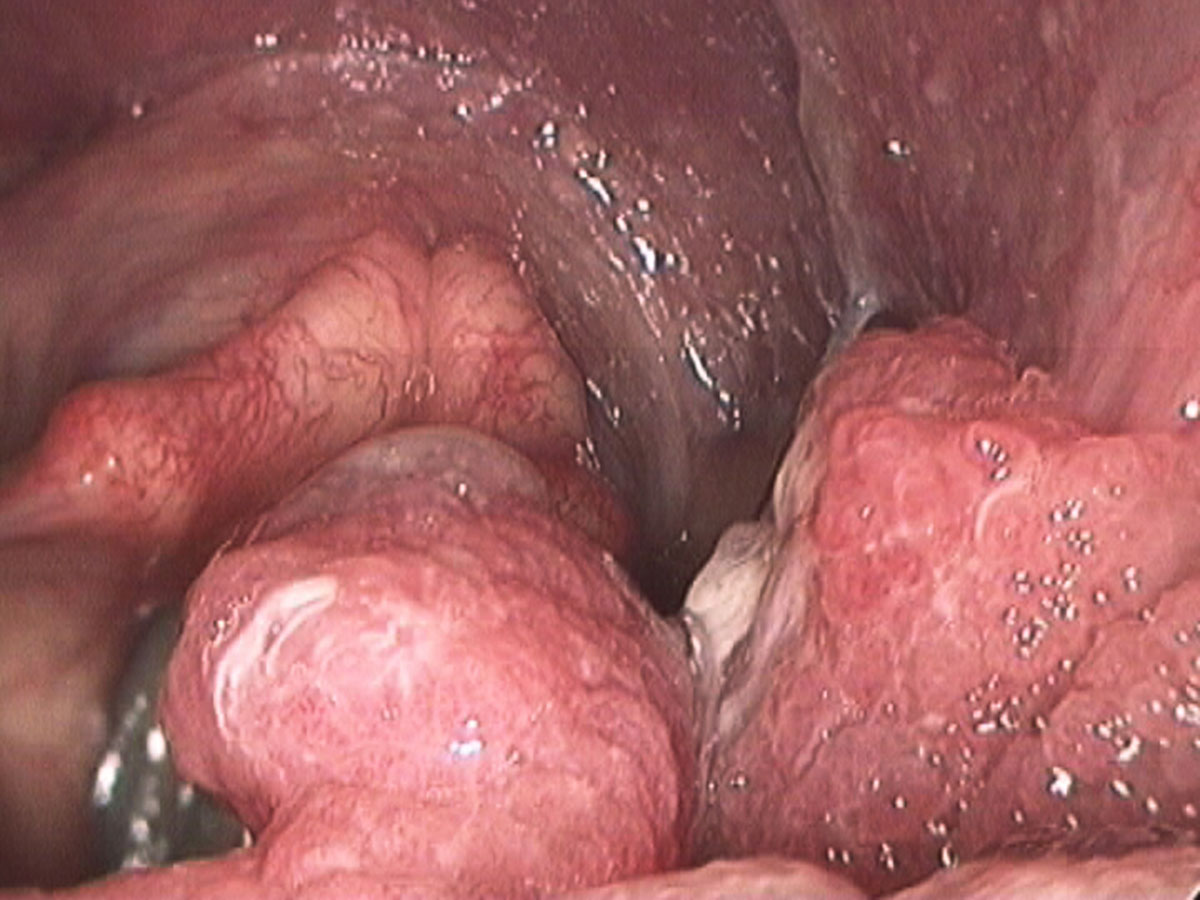

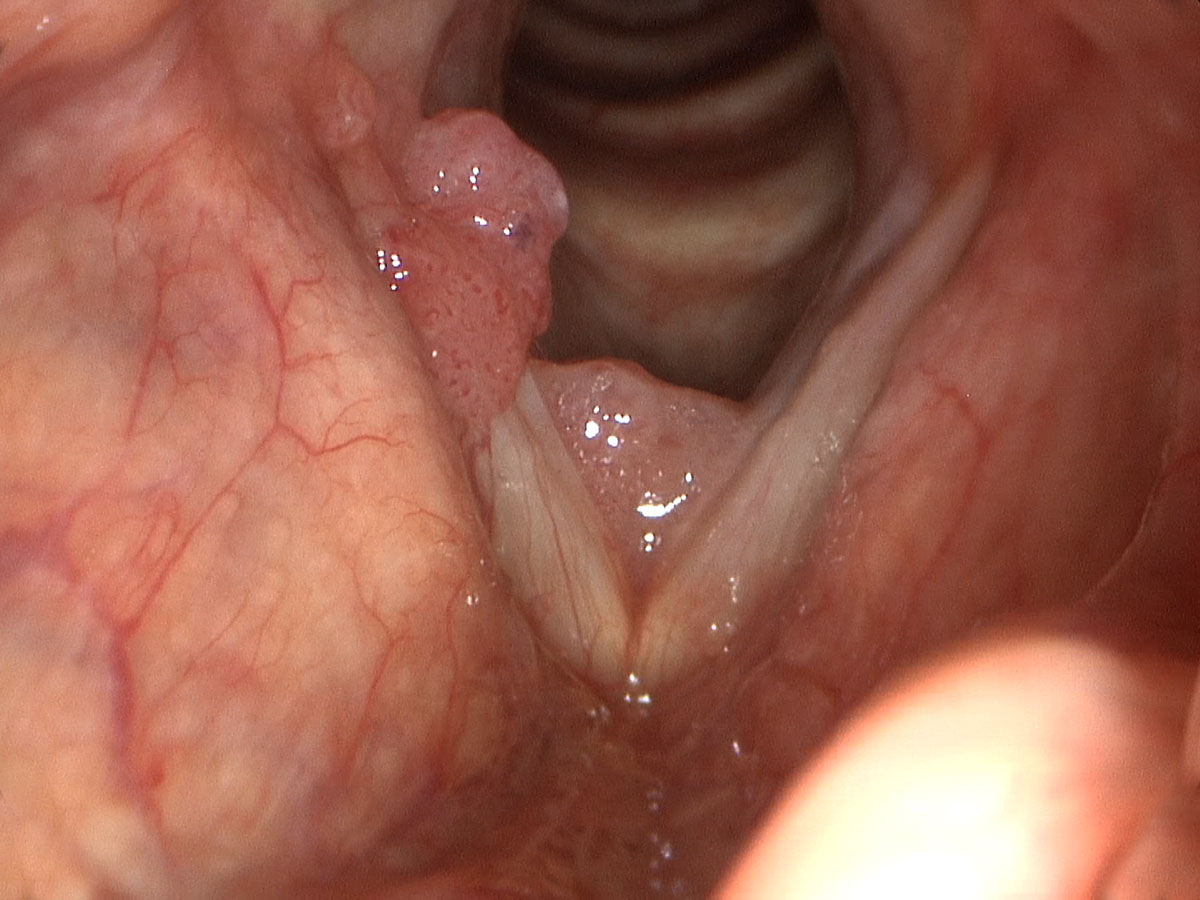

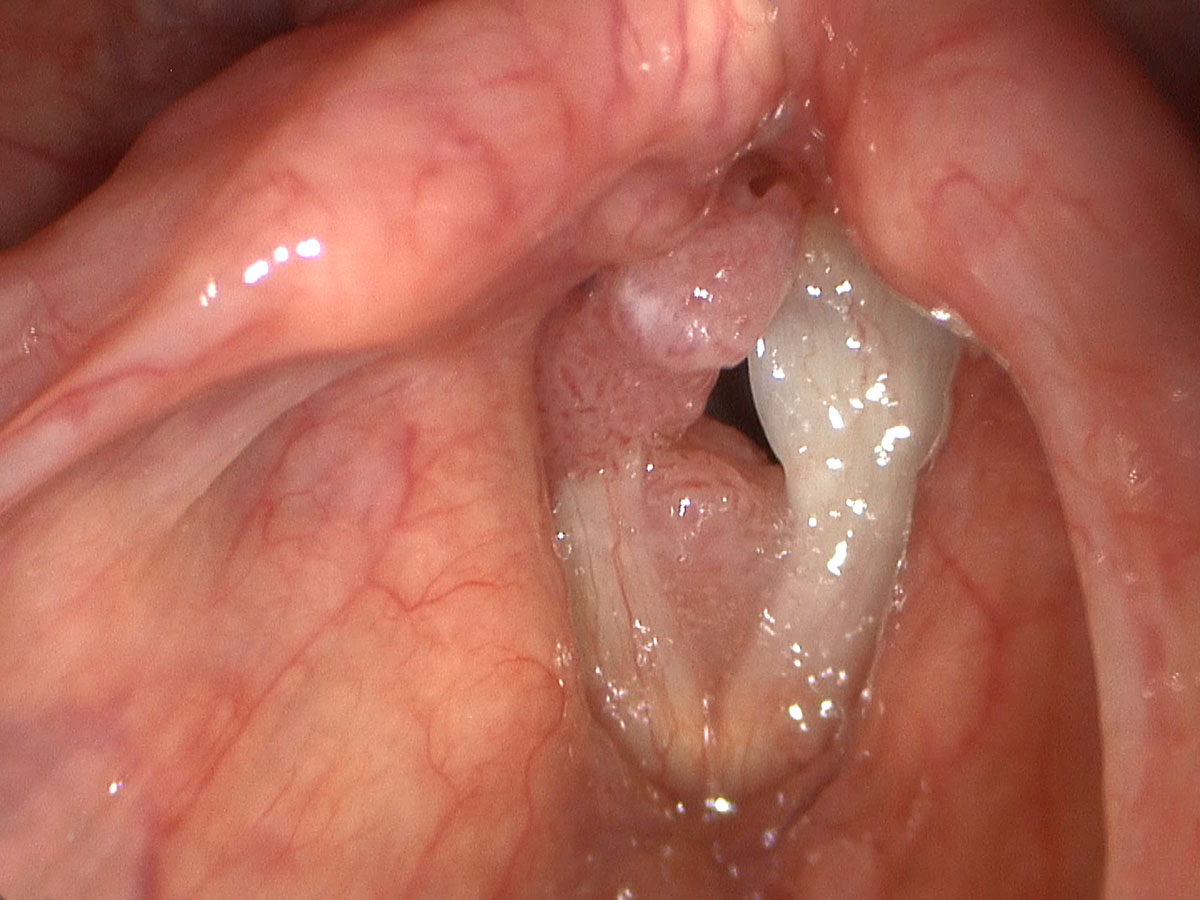

The papillomatosis lesions develop on the mucosa, which is the thin surface lining of the larynx. This lining is approximately five cell layers thick and is transparent. Given that the papilloma grows from this layer, treatment approaches should be aimed at eradicating the disease but providing maximal preservation of the delicate layered microstructure beneath the epithelium, that is, the critical structures involved in sound production and your voice.

As papilloma tends to affect the vocal cords predominantly, it very quickly can lead to hoarseness of the voice. This comes from alteration to the surface pliability and the ability for the vocal cords to close completely. These two criteria are critical for normal sound production. If papilloma becomes extensive enough it can actually compromise the airway in the larynx and lead to shortness of breath and airway obstruction.

The most advanced and innovative techniques in managing laryngeal papilloma involve the use of a group of lasers called angiolytic lasers. The pulsed KTP laser is the most effective in this class and is highly specialised for laryngeal papilloma. It remains by far the most efficient and effective way to manage laryngeal papilloma. It does this by targeting the microcirculation within the papilloma and ablating all the feeding blood vessels. In turn, the papillomatous lesions are involuted and then suctioned free during the procedure. As the KTP laser energy is exclusively taken up within the blood vessels of the papilloma, there is maximal preservation of the healthy underlying tissue of the vocal fold that is critical to voice. The laser is also able to ablate small feeding vessels on the periphery of the papilloma that can further reduce the chance for recurrence. As such, the KTP laser treatment offers extremely effective removal of the papilloma but allows for resumption of normal voice once healed. In Dr Broadhurst’s patients those that have undergone exclusive KTP laser treatment and required multiple procedures, remain with an entirely normal voice between flare-ups. Unfortunately, this is not the case in patients treated with other modalities. Due to the inability of the carbon dioxide laser and the microdebrider shaving instruments to preserve the underlying layered microstructure of the vocal fold, permanent hoarseness is the usual outcome for repeated procedures using these techniques.

An excellent approach to deciding on the management for a patient in Dr Broadhurst’s mind is asking himself this question “if this was my vocal cord, how would I like it treated?”. In applying this question to all the conditions treated by Dr Broadhurst, patients can rest assured they are getting what Dr Broadhurst feels is the optimal treatment for their condition.

In addition to the use of KTP laser, Dr Broadhurst also injects an agent into the vocal cords that blocks blood vessel growth. Avastin (bevacizumab) has been studied at the Centre for Laryngeal Surgery and Voice Restoration in Boston where Dr Broadhurst worked for two years. The results that Dr Broadhurst observed and has carried over into his own practice in Australia have been extremely encouraging. There certainly appears to be a significant response to the use of this medication in a majority of papilloma patients. It was initially used in the ophthalmology setting by injecting it for wet macular degeneration. Given that it has safety for injection into the eye, it is no surprise that it has proved extremely safe for injection into the vocal folds and the larynx.

Other technologies available, aside from carbon dioxide laser and microdebrider shaving, include Coblation technology. Dr Broadhurst has strong reservations about the use of any of those modalities, as they are not as precise in ablating and removing papilloma while maximally preserving the delicate soft tissue of the vocal fold. Patients can be shown before and after high definition video endoscopies of patients with papilloma treated by the typical KTP laser techniques. This is used to help educate patients on various treatment options, being able to then develop a sense for the expected outcome.

The KTP laser also provides the ability to treat patients in the office setting as an outpatient. Due to its very fine flexible glass fibre that carries the laser energy, a video endoscope or a curved metal cannula can be used to deliver the laser fibre onto the laryngeal papilloma. This can be done reliably under local anaesthetic without any sedation in the office setting or as an outpatient admission. Either way, it allows patients to avoid repeated general anaesthetics while controlling their papilloma. This greatly reduces the morbidity of repeated general anaesthetics and saves a substantial amount of patient time and resources. There is also substantial cost saving involved in this procedure in some settings.